It was April 1971. General Franco was still alive. It would be another five years before he left this world and his body was taken to the Valle de los Caídos. I was fifty years younger than I am today and had arrived in Barcelona from my native Andalusia not long before. I was young, very young, full of anger and strength to try and find ways of putting an end to the state of marginalisation and abandonment in which the majority of Spanish gypsies lived. And I took advantage of the invitation from Caritas Diocesana de Barcelona in order to settle into the Ciudad Condal and from here start what would what would soon be the embryo of the powerful gypsy movement that we have in our country today.

The Church or the Falange

For many years, especially during the final years of Francoism, there were only two institutions which enjoyed a certain freedom to say things that the ruling Regime would not like. Denouncing injustices, demanding a more prominent role for workers in decision making, highlighting the extreme poverty in which thousands of Spanish people were still living would earn those who led this struggle a prison sentence. I knew this well because they had warned me on occasion. For this reason, as can be easily understood, I preferred to seek refuge under the protection under the umbrella of the Church and this is how some committed gypsies began to shed the load that had for centuries weighed upon us, condemning us to the most painful marginalisation: poverty and illiteracy.

How the London Congress Was Conceived

This explained why one day I received an invitation from the self-proclaimed International Gypsy Committee, based in Paris and led by brothers Vanko and Léulea Rouda. A few months before I was visited by Donald Kenrick, an Englishman who appeared one day in Barcelona with his daughter, a young girl who at that time would have been 12 or 13 years old. Both presented the typical preconceived image that we had of English people. Golden blond hair, friendly, ceremonial in their ways, and decked out in clothes that showed an unkempt elegance. He told me that he was preparing an international meeting of gypsy leaders from all over the world which gypsies from the Soviet Union would attend for the first time. I admit that this announcement excited me because it felt that this would be the opportunity to know first-hand what life was like for gypsies in the rest of the world. Donald Kenrick was an exceptional linguist who could translate more than fifty languages and spoke some thirty fluently, including Catalan. In addition to him two influential public figures contributed to this project becoming a reality with much success: they were Dr Thomas Acton, a professor at the University of Oxford and an expert in gypsy language and culture, and Grattan Puxon, an English activist who held the post of Secretary General of the Congress.

UNESCO was left to seize the organisation of the Congress

Vanko Rouda was determined to hold a major Congress at the UNESCO Palace in Paris, in which the world’s most important gypsies in Romani intelligentsia would participate. It was his intention that the Council of Europe would take the first step towards the institutional acknowledgement of gypsy people. But the talks dragged on which led Grattan Puxon to convince the members of the Gypsy Council of Great Britain, founded in 1966, to go to London where the much talked-about International Congress was to be held. Somebody described Puxon’s initiative as a ‘coup d’état’. And it was, but its consequences were advantageous and very positive. In doing so he surprised members of the International Gypsy Committee in Paris by organising a large cultural festival on Easter Monday in 1971 at Hampstead Heath, which is one of the most beautiful and semi-wild parks on the outskirts of London, occupying more than 320 hectares. This aroused media interest in those who had made known the importance of this global gathering which would later take place in Chelsfield.

The presence of the ‘gadchés’ had to be banned from the Congress

The organisers were very clear that if any non-gypsy researchers, historians, sociologists or members of humanitarian or charitable organisations were to take part in the Congress they would unquestionably prejudice its results and would inhibit those gypsies present from speaking with complete freedom about their present life and, above all, the future that they wanted for our people. And they were successful, to the extent that the food served to us during the days of the Congress was prepared by a gypsy cook from a London hotel who took some of his holiday leave to attend the Congress and make some food for us. But we could not disregard those persons who were interested in accompanying us or simply wanted to know of our intentions first-hand. To this end, Thomas Acton was commissioned to organise an academic conference at the University of Oxford before the formal opening of the Congress. Thus, those of us who took part in the discussions at Chelsfield were free from any outside influence to interpret how gypsies have genuinely lived out our past history and how we intended to approach our future.

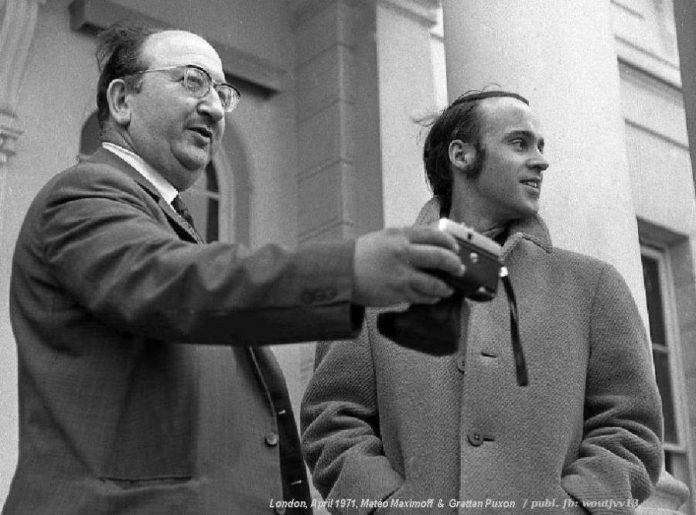

Besides Dr Acton, who was our best speaker at the Congress, this academic meeting was attended on our part by the great gypsy writer and brilliant storyteller Mateo Maximoff, one of whose novels Le Prix de La Liberté had been translated into more than fifteen languages, participated in this academic meeting, as well as Jan Kochanowski, our most highly regarded linguist and expert in the dialect variants of Baltic, Ukrainian and Russian gypsies. Ian Hancock, one of our most illustrious representatives, professor at the University of Texas and a great linguist who was our representative at the United Nations under the presidency of Bill Clinton also attended the conference at the University of Oxford.

April 8th, the best showcase of our presence in the world

It was at the 1990 International Romani Union Congress, in Warsaw, when we decided that April 8th was the most noted date for establishing an International Romani Day. On that date in 1971, a new era in the thousand-year history of the gypsy people began. And today, almost 30 years after making this agreement and 48 years since the holding of the Congress in London we are able to ensure that the International Romani Day is on the agenda of all of the world’s democratic governments. And our country, a pioneer in so many new things relating to gypsies and Spanish gypsies, once again leads the countries of the European Union. The Spanish government, for its part, in the Council of Ministers of 6th April 1998 approved the acknowledgment of April 8th as International Romani Day. On this day the rivers of Spain, as well as many others in France, the United Kingdom, Italy, Germany, the Americas and even in Russia flowed carrying flower petals on their surface. A symbol of beauty and colour that has crossed frontiers without asking anybody for permission because the waters have no owner and borders are an invention that one day should play a role other than that of the repression of freedom.

The 1971 Congress in London has now passed into history. But if should it occupy a prominent place in the consciences of all civilised humans for any reason it should be for establishing a flag which has only two colours. A blue stripe above which symbolises the only roof that protects all of we gypsies in the world, and a green stripe at the bottom to show that beyond the harsh eyes of exclusionary nationalisms, we are citizens of the world. A simple faith, fraternal and beautiful that all citizens, gypsy or not, should make their own.

This English translation has been possible thanks to the PerMondo project: Free translation of website and documents for non-profit organisations. A project managed by Mondo Agit. Translator: Andrew Agrafojo.

You can read our last year comment by clicking on the following link: https://unionromani.org/en/2018/04/09/today-is-our-day/